Empty columned hall, mid-morning, of Isfahan’s Jameh Mosque, built as a mosque in around 771 after the Arab conquest, and added to by successive ruling dynasties.

‘Nearly every significant architectural and decorative trend of medieval period in Persian history found its monumental representation in this mosque. In fact, so richly diverse, artistically accomplished and technologically inventive are the building and decorative strategies employed in this mosque that it has served as a blueprint for medieval Persian architecture in general.’

Sussan Babaie with Robert Haug, “Isfahan x. Monuments (3) Mosques”, Encyclopedia Iranica

“This is the perfection of architecture, attained … by their chivalry of balance and proportion. And this small interior comes nearer to that perfection than I would have thought possible outside classical Europe.”

- Robert Byron (1937), The Road to Oxiana. From his diary entry made on 16 March 1934.

Fresh late-night flatbreads (sangak), under the gaze of Ayatollahs Khamenei and Khomenei.

Chewy, stretchy, airy bread, that hardens all too quickly - buy it fresh or not at all. Like a thinner version of laffa bread. One of the bakers waved me in after he noticed me outside.

Probably not what Tavernier saw in 1653 - but Iranian traffic has more than replaced the dangers of being run down by a horse: road accidents cause 20,000 deaths and 800,000 injuries annually.

‘For the men are all upon the false gallop in the streets, without any fear of hurting the children: by reason that the children are not suffered to play in the streets like ours, but as soon as ever they come from school, they sit down by their parents, to be instructed by them in their profession.’

- Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1678), The Six Voyages of John Baptista Tavernier...through Turkey into Persia (translated by John Phillips). From his third stay in Isfahan, in 1653.

Goldfish and flowers for sale, a few days before the beginning of the Iranian New Year, Nowruz. Both are elements of the haft-sin, a table of things assembled in the house for the two-week new year holiday.

‘… the mullahs of the College had quietly gone one better. From the parapet of the great portal they had let down three cut-glass chandeliers, whose pale candles, flickering against the black void of the arch, revealed three globes of goldfish suspended between them.’

- Robert Byron (1937), The Road to Oxiana. From his visit to the city in March 1934.

Pre-dawn in the middle of the great meydan (public square). In the foreground, a large pool, dry due to the perennial water shortage.

‘It has many great and notable antiquities amongst the which the chiefest is a square cisterne, with cleere and sweete water, very good to drink, round about the which is a goodly wharfe set with pillars and vaults: where are innumerable rooms and places for merchants to bestow their merchandise.’

- Josafa Barbaro and Ambrogio Contarini (1873), Travels to Tana and Persia, translated by William Thomas. This is from Barbaro’s visit to Isfahan in 1474.

The Zayanderud (‘life giver’) river, dry, except when the government decides to release water from the dams upstream. These swan-boats lie beached near the city’s central footbridge.

‘Imagine Paris without the Seine, London without the Thames. Isfahan, with just over a million people, may be smaller, but its people are no less passionate about the Zaindeh River, or Zaindeh-Rud, as it is called in Persia.’

- Article by Amy Waldman published in the New York Times on 16 August 2001.

I would have thought it was impossible for a country to have so many shoe stores.

Entrance to the grand bazaar from the north end of the meydan.

‘From the end of the porticos that touch the north side of the Mosque, live the shop-keepers that sell sowing-silk, and small manufactures of silk, as ribbons, laces, garters, and other things of the same nature. From the mosque to the other end, are all turners, that make cradles for children, and spinning-wheels. There are also some cotton-beaters, that make quilted coverlets. Without the porticos are none but smiths, that make scythes, hammers, pincers, nails and such like things; with some few cutlers.’

- Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1678), The Six Voyages of John Baptista Tavernier...through Turkey into Persia (translated by John Phillips). From his third stay in Isfahan, in 1653. I’ve tidied up the old English.

‘This entrance complex corrects the alignment of the mosque by twisting the axis of approach, but it also provides a liminal space passage through which provides the worshipper the opportunity, visually and spatially mediated, to leave the mundane world behind before entering the sanctified space of the mosque.’

- Susan Babaie and Robert Haug, “Isfahan X. Monuments – Mosques”, Enyclopedia Iranica

A wall of the Darb-i Imam Shrine, completed in 1453. An almost aperiodic pattern adorns the spandrel (the triangular bits at the top of the arch) second from photo left. Mathematicians first proved aperiodic patterns existed in the 1960s. A plain-English introduction to aperiodic patterns can be accessed here.

‘… the efficiency of this method is illustrated by the high quality of the pattern at the Darb-i Imam shrine—when it is mapped to Penrose tiles, there are only 11 defects among 3700 tiles—it is the most mathematically complex pattern yet discovered’.

- Sebastian R. Prange, (2009) The Tiles of Infinity, Saudi Aramco World

Allahverdi Khan Bridge, popularly known as Siosepol (the bridge of thirty three spans).

‘At either end [of the bridge], from day to day and year to year, there are two Persians seated on the ground…they rose at our approach, and from one of the arches brought forward a lighted kalian [hookah], all ready for indulgence in the favourite form of smoking … the traveller, if he pleases, takes the pipe, and after smoking from one end of the bridge to the other, leaves it with the second pair of pipe bearers’.

Arthur Arnold (1877), Travels through Persia by Caravan. From his visit to Isfahan in around 1876.

Poets sit under the bridge at night, singing verse.

‘Wheresoever beauty files

Follow her on eager wings

Beauteous wild imaginings.’

- Sonnets from Hafez and Other Verses, translated by Elizabeth Bridges

‘The whole Char Bagh [main boulevard, that leads onto the Siosepol] was illuminated as I walked back to Wishaw’s house across the river. Tiers of lamps and candles were ranged at intervals under the trees, great wedding-cakes of light thirty feet high, draped in red and backed with gilt mirrors.’

- Robert Byron (1937), The Road to Oxiana. From his diary entry made on 16 March 1934.

Food. The chicken is usually fine; the mutton (you rarely get lamb) is, well, muttony, which is fine in stews, but not as much in the kebabs.

You can try the Isfahani Biryani, which bears no resemblance to the Indian Biryani, and is perfect in the same way a Halal Snack Pack is perfect when you’re sloshed at two in the morning. Pity it’s a dry country.

More unique is the Khoresht-i Mast, a vivid yellow, sweet dessert yoghurt made with sheep’s neck. Now that’s delicious.

Or find a make-your-own falafel sandwich shop. Falafel isn’t Iranian, but it’s tough to pass up dinner for a dollar.

Chaharshanbe Suri, the last Wednesday before the Iranian New Year, Nowruz. I sat with these two and set off firecrackers, watched fireworks go off, swapped cigarettes, and flicked around charcoal embers.

‘For the first two years after the Revolution of [1978-79] the government prohibited celebration of Caharsanba-sūrī, declaring it a relic of fire worship, but the people persisted in lighting the fires, and eventually the authorities relented; the practice is now tolerated.’

- Manouchehr Kasheff and ʿAlī-Akbar Saʿīdī Sīrjānī, “CAHARSANBA-SŪRĪ,” Encyclopaedia Iranica

On the dry river, Chaharshanbe Suri.

‘One or two days before the last Wednesday of the year people go out to gather bushes … in the cities they buy brushwood. In the afternoon before the start of Čahāršanba-sūrī the brushwood is laid out in the yard of the house, if it is spacious enough, or in a village square or city street; it is arranged in one, three, five, or seven bundles (always an odd number) spaced a few feet apart. At sunset or soon after the bundles are set alight, and while the flames flicker in the dusk men, women, and children jump over them, singing sorḵī-e to az man, zardī-e man az to “[let] your ruddiness [be] mine, my paleness yours,” or the equivalent in local dialects’.

- Manouchehr Kasheff and ʿAlī-Akbar Saʿīdī Sīrjānī, “ČAHĀRŠANBA-SŪRĪ,” Encyclopaedia Iranica

Empty columned hall, mid-morning, of Isfahan’s Jameh Mosque, built as a mosque in around 771 after the Arab conquest, and added to by successive ruling dynasties.

‘Nearly every significant architectural and decorative trend of medieval period in Persian history found its monumental representation in this mosque. In fact, so richly diverse, artistically accomplished and technologically inventive are the building and decorative strategies employed in this mosque that it has served as a blueprint for medieval Persian architecture in general.’

Sussan Babaie with Robert Haug, “Isfahan x. Monuments (3) Mosques”, Encyclopedia Iranica

“This is the perfection of architecture, attained … by their chivalry of balance and proportion. And this small interior comes nearer to that perfection than I would have thought possible outside classical Europe.”

- Robert Byron (1937), The Road to Oxiana. From his diary entry made on 16 March 1934.

Fresh late-night flatbreads (sangak), under the gaze of Ayatollahs Khamenei and Khomenei.

Chewy, stretchy, airy bread, that hardens all too quickly - buy it fresh or not at all. Like a thinner version of laffa bread. One of the bakers waved me in after he noticed me outside.

Probably not what Tavernier saw in 1653 - but Iranian traffic has more than replaced the dangers of being run down by a horse: road accidents cause 20,000 deaths and 800,000 injuries annually.

‘For the men are all upon the false gallop in the streets, without any fear of hurting the children: by reason that the children are not suffered to play in the streets like ours, but as soon as ever they come from school, they sit down by their parents, to be instructed by them in their profession.’

- Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1678), The Six Voyages of John Baptista Tavernier...through Turkey into Persia (translated by John Phillips). From his third stay in Isfahan, in 1653.

Goldfish and flowers for sale, a few days before the beginning of the Iranian New Year, Nowruz. Both are elements of the haft-sin, a table of things assembled in the house for the two-week new year holiday.

‘… the mullahs of the College had quietly gone one better. From the parapet of the great portal they had let down three cut-glass chandeliers, whose pale candles, flickering against the black void of the arch, revealed three globes of goldfish suspended between them.’

- Robert Byron (1937), The Road to Oxiana. From his visit to the city in March 1934.

Pre-dawn in the middle of the great meydan (public square). In the foreground, a large pool, dry due to the perennial water shortage.

‘It has many great and notable antiquities amongst the which the chiefest is a square cisterne, with cleere and sweete water, very good to drink, round about the which is a goodly wharfe set with pillars and vaults: where are innumerable rooms and places for merchants to bestow their merchandise.’

- Josafa Barbaro and Ambrogio Contarini (1873), Travels to Tana and Persia, translated by William Thomas. This is from Barbaro’s visit to Isfahan in 1474.

The Zayanderud (‘life giver’) river, dry, except when the government decides to release water from the dams upstream. These swan-boats lie beached near the city’s central footbridge.

‘Imagine Paris without the Seine, London without the Thames. Isfahan, with just over a million people, may be smaller, but its people are no less passionate about the Zaindeh River, or Zaindeh-Rud, as it is called in Persia.’

- Article by Amy Waldman published in the New York Times on 16 August 2001.

I would have thought it was impossible for a country to have so many shoe stores.

Entrance to the grand bazaar from the north end of the meydan.

‘From the end of the porticos that touch the north side of the Mosque, live the shop-keepers that sell sowing-silk, and small manufactures of silk, as ribbons, laces, garters, and other things of the same nature. From the mosque to the other end, are all turners, that make cradles for children, and spinning-wheels. There are also some cotton-beaters, that make quilted coverlets. Without the porticos are none but smiths, that make scythes, hammers, pincers, nails and such like things; with some few cutlers.’

- Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1678), The Six Voyages of John Baptista Tavernier...through Turkey into Persia (translated by John Phillips). From his third stay in Isfahan, in 1653. I’ve tidied up the old English.

‘This entrance complex corrects the alignment of the mosque by twisting the axis of approach, but it also provides a liminal space passage through which provides the worshipper the opportunity, visually and spatially mediated, to leave the mundane world behind before entering the sanctified space of the mosque.’

- Susan Babaie and Robert Haug, “Isfahan X. Monuments – Mosques”, Enyclopedia Iranica

A wall of the Darb-i Imam Shrine, completed in 1453. An almost aperiodic pattern adorns the spandrel (the triangular bits at the top of the arch) second from photo left. Mathematicians first proved aperiodic patterns existed in the 1960s. A plain-English introduction to aperiodic patterns can be accessed here.

‘… the efficiency of this method is illustrated by the high quality of the pattern at the Darb-i Imam shrine—when it is mapped to Penrose tiles, there are only 11 defects among 3700 tiles—it is the most mathematically complex pattern yet discovered’.

- Sebastian R. Prange, (2009) The Tiles of Infinity, Saudi Aramco World

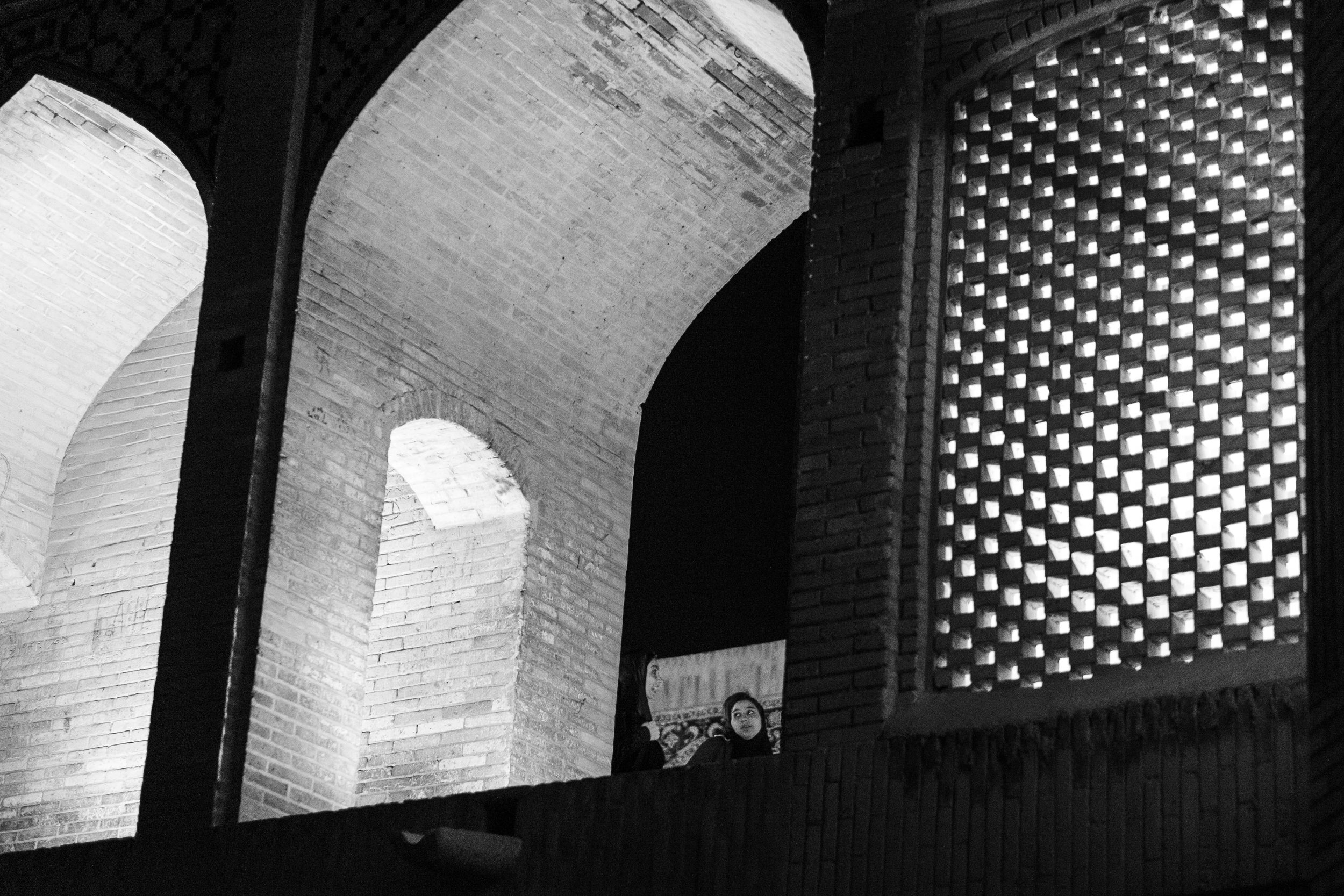

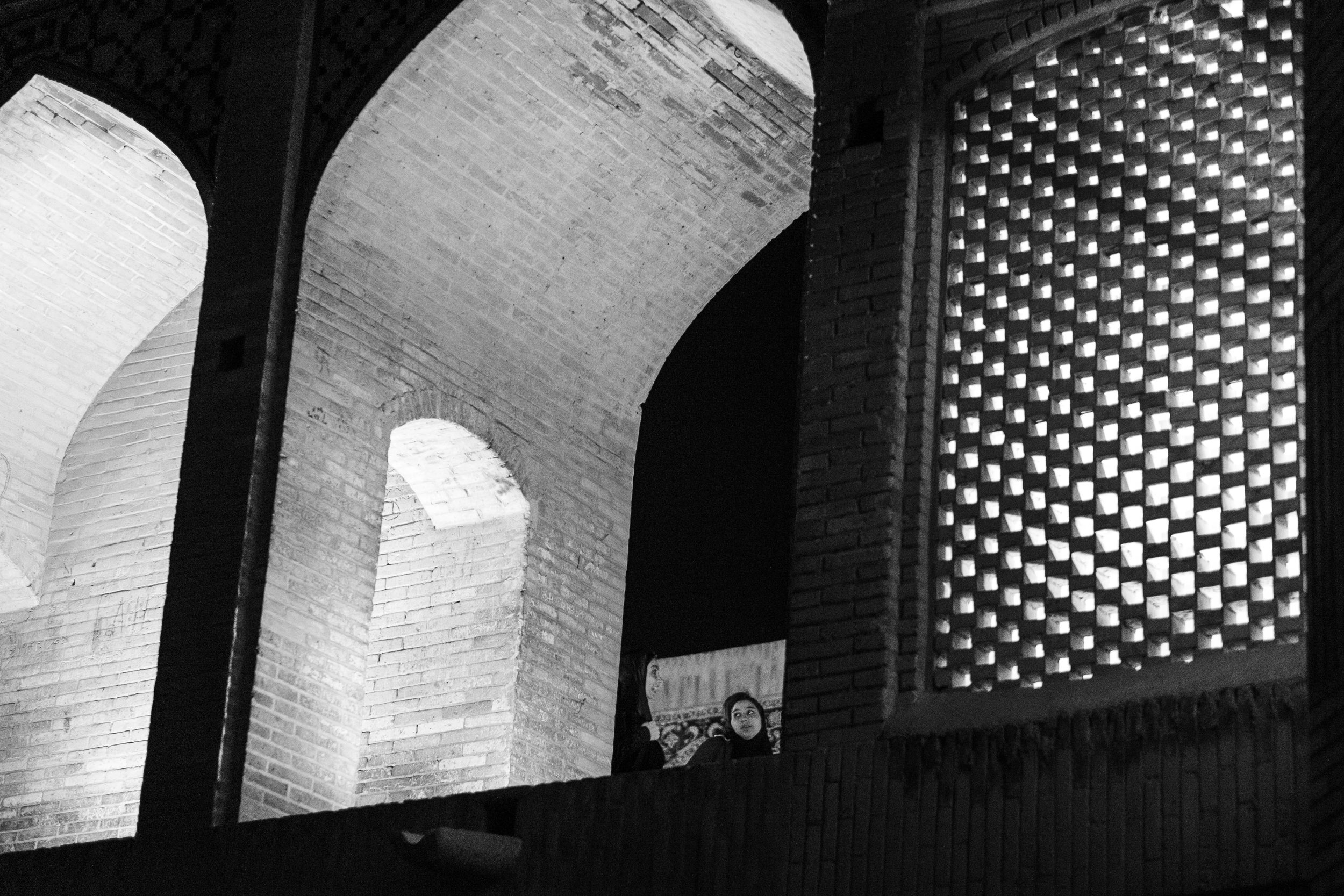

Allahverdi Khan Bridge, popularly known as Siosepol (the bridge of thirty three spans).

‘At either end [of the bridge], from day to day and year to year, there are two Persians seated on the ground…they rose at our approach, and from one of the arches brought forward a lighted kalian [hookah], all ready for indulgence in the favourite form of smoking … the traveller, if he pleases, takes the pipe, and after smoking from one end of the bridge to the other, leaves it with the second pair of pipe bearers’.

Arthur Arnold (1877), Travels through Persia by Caravan. From his visit to Isfahan in around 1876.

Poets sit under the bridge at night, singing verse.

‘Wheresoever beauty files

Follow her on eager wings

Beauteous wild imaginings.’

- Sonnets from Hafez and Other Verses, translated by Elizabeth Bridges

‘The whole Char Bagh [main boulevard, that leads onto the Siosepol] was illuminated as I walked back to Wishaw’s house across the river. Tiers of lamps and candles were ranged at intervals under the trees, great wedding-cakes of light thirty feet high, draped in red and backed with gilt mirrors.’

- Robert Byron (1937), The Road to Oxiana. From his diary entry made on 16 March 1934.

Food. The chicken is usually fine; the mutton (you rarely get lamb) is, well, muttony, which is fine in stews, but not as much in the kebabs.

You can try the Isfahani Biryani, which bears no resemblance to the Indian Biryani, and is perfect in the same way a Halal Snack Pack is perfect when you’re sloshed at two in the morning. Pity it’s a dry country.

More unique is the Khoresht-i Mast, a vivid yellow, sweet dessert yoghurt made with sheep’s neck. Now that’s delicious.

Or find a make-your-own falafel sandwich shop. Falafel isn’t Iranian, but it’s tough to pass up dinner for a dollar.

Chaharshanbe Suri, the last Wednesday before the Iranian New Year, Nowruz. I sat with these two and set off firecrackers, watched fireworks go off, swapped cigarettes, and flicked around charcoal embers.

‘For the first two years after the Revolution of [1978-79] the government prohibited celebration of Caharsanba-sūrī, declaring it a relic of fire worship, but the people persisted in lighting the fires, and eventually the authorities relented; the practice is now tolerated.’

- Manouchehr Kasheff and ʿAlī-Akbar Saʿīdī Sīrjānī, “CAHARSANBA-SŪRĪ,” Encyclopaedia Iranica

On the dry river, Chaharshanbe Suri.

‘One or two days before the last Wednesday of the year people go out to gather bushes … in the cities they buy brushwood. In the afternoon before the start of Čahāršanba-sūrī the brushwood is laid out in the yard of the house, if it is spacious enough, or in a village square or city street; it is arranged in one, three, five, or seven bundles (always an odd number) spaced a few feet apart. At sunset or soon after the bundles are set alight, and while the flames flicker in the dusk men, women, and children jump over them, singing sorḵī-e to az man, zardī-e man az to “[let] your ruddiness [be] mine, my paleness yours,” or the equivalent in local dialects’.

- Manouchehr Kasheff and ʿAlī-Akbar Saʿīdī Sīrjānī, “ČAHĀRŠANBA-SŪRĪ,” Encyclopaedia Iranica