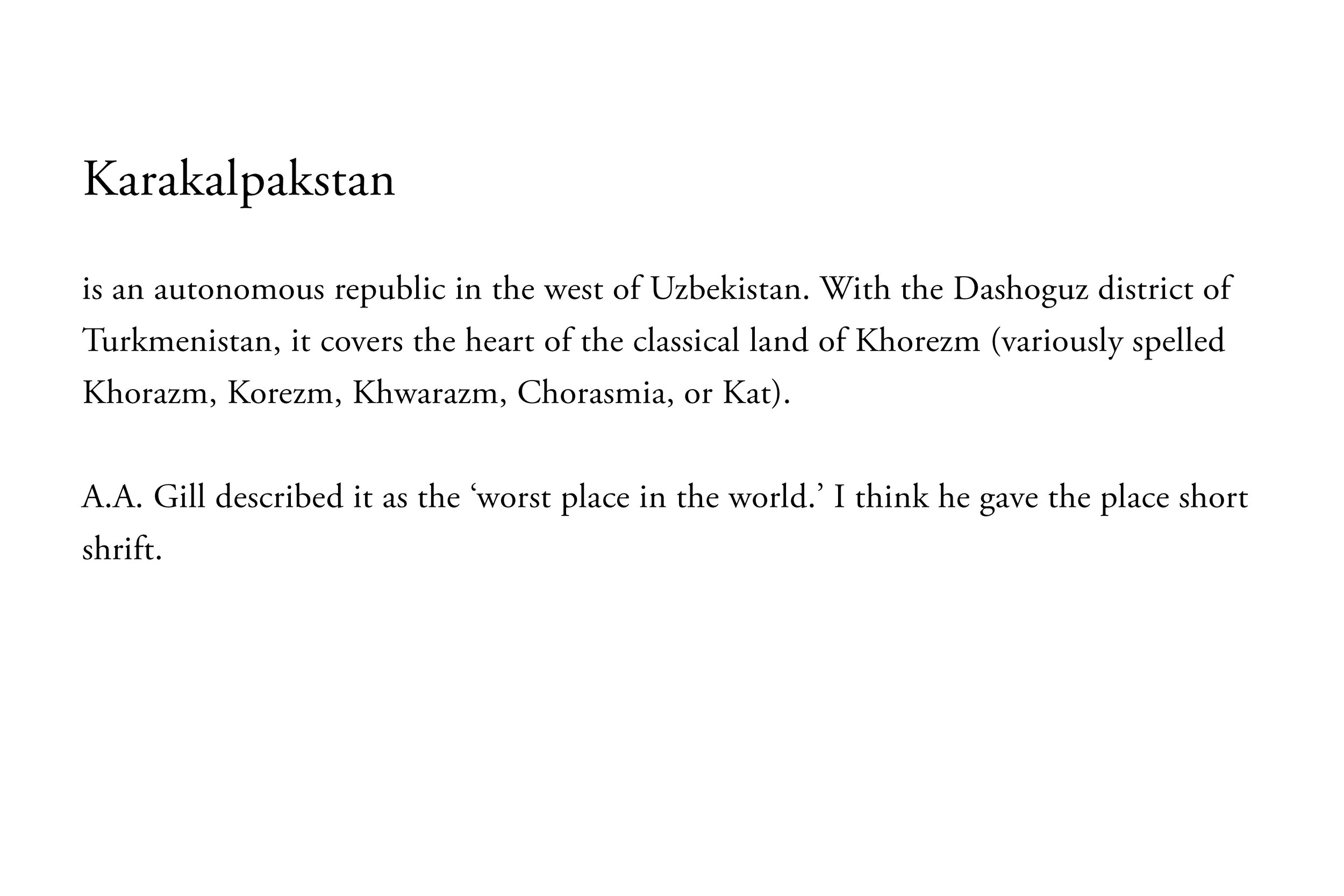

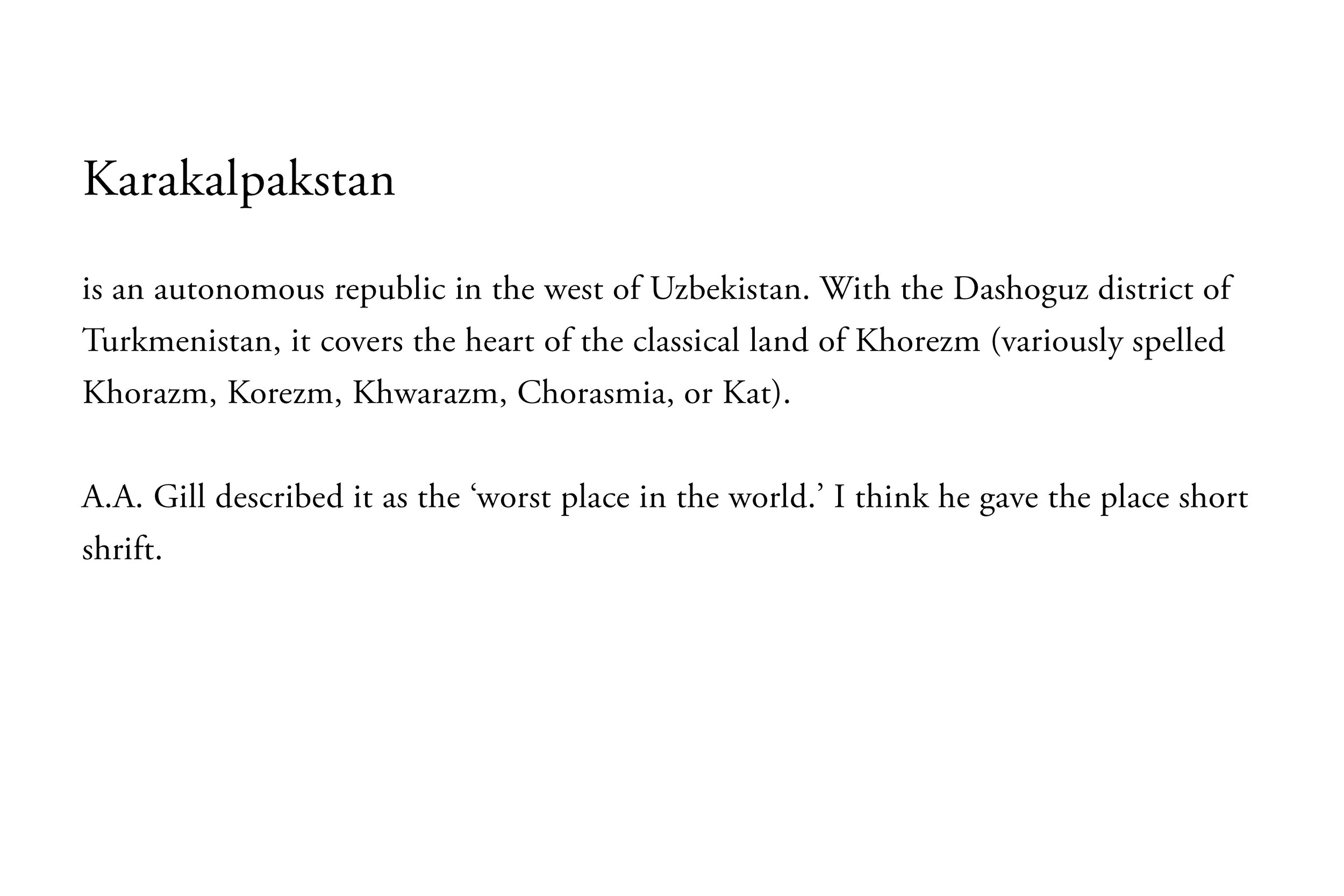

By a canal, looking towards the mosque, in Nukus.

‘Irrigation made arable land a valuable and scarce commodity…[in] centuries of work on the land, surveyor-practitioners in the various oases had worked out methods of measuring regular and irregular fields…it was a natural step for Central Asians to compile the known techniques of geometry, work out the first system of practical algebra, and create the field of trigonometry. The major step in this direction occurred in the ninth century, on the basis of accumulated experience of Khwarazm, the most intensely irrigated region’.

- S. Frederick Starr (2013), Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane, Princeton University Press

Bazaar in Nukus.

‘They reached a fertile and well-watered place,

Possessed of every strength and natural grace:

The setting’s natural limit was the sea,

A highway marked the inland boundary,

To one side mountains reared above the plain,

A place of hunting grounds, and wild terrain;

The streams, the groves of trees, made weary men

Feel that their ancient hearts were young again.’

- Abdolqasem Ferdowsi, Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, translated by Dick Davis. This verse describes the Iranian hero Seyavash founding a city somewhere in Turkestan, at the invitation of Afraysiab the Turk.

Bazaar in Nukus.

‘The tenth-century geographer Mukadasi has left a detailed list of the commodities traded by the merchants of Khorezm…locally produced commodities included: ‘grapes, many raisins, almond pastry, sesame, fabrics of striped cloth, carpets, blanket cloth, satin for royal gifts, coverings of mulham fabric, locks, Aranj fabrics, bows which only the strongest could bend, rakhbin [cheese], yeast, fish, boats' …[also] watermelons so succulent that they were packed into lead containers lined with snow and conveyed to the caliphs of Baghdad…a single melon was worth 700 dirhams - equivalent to more than 2 kg of silver.’

- Jonathan Tucker (2015), The Silk Road: A Travel Companion, I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd

Bazaar in Nukus, fifty kilometres from old Gurganj.

‘Despite its utter destruction, within 100 years Gurganj had risen from the ashes…by the early fourteenth century, Gurganj had been rebuilt to serve the caravans travelling to the Golden Horde territory in the Volga region. Ibn Battuta described newly revived Gurganj as a vigorous commercial centre, ‘the largest, greatest, most beautiful and most important city of the Turks, shaking under the weight of its populations, with bazaars so crowded that it was difficult to pass.’’

- Jonathan Tucker (2015), The Silk Road: A Travel Companion, I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd

Traintracks near the station in Khujayli, with the ever-present salted ground in the foreground.

‘“We are destroying ourselves,” said the 61-year-old farmer in Khujayli. “Why are we planting cotton, and what are we getting from it? We never ask those questions.”’

- Farmer quoted by Sabrina Tavernise, ‘Old Farming Habits Leave Uzbekistan a Legacy of Salt’, New York Times article on 15 June 2008

Petrol station surrounded by salted land in Nukus.

‘Before committing to large and expensive drainage projects, it is essential to remove the distortions in relative prices of crops and water that generate a large part of the problem.’

- Kyle, Steven C. & Chabot, Phillippe (1997), Agriculture in the Republic of Karakalpakstan and Khorezm Oblast of Uzbekistan.

The distortions included unrealistic cotton yield targets set by the state, input (water, fuel, fertiliser, and labour) subsidies, and farmers having to sell their cotton to the state at a discount.

Go-kart track in Nukus.

‘The farmer in Khujayli recalled a car trip with his father in the winter of 1954 near the city of Muynoq that began with a crossing of miles of Aral Sea ice. Now the shore is more than 50 miles away from the city. In the 1970s, his grandfather’s apricot trees died. Salt eats away at shoes here and turns bricks white.’

- Sabrina Tavernise, ‘Old Farming Habits Leave Uzbekistan a Legacy of Salt’, New York Times article on 15 June 2008

The dry riverbed of the Amu Darya near Nukus.

‘Shallow groundwater contributes to salt accumulation through capillary rise, and results in the accumulation of salts at the soil surface ... In agricultural fields, the “critical depth”, which results in the accumulation of salts due to capillary rise, is in the range 1.5-2.0 m below the surface ... the groundwater depth in Khorezm was above the critical level throughout the growing season.’

- Ibrakhimov, Mirzakhayot & Park, Soojin & Vlek, Paul. (2004). Development of groundwater salinity in a region of the lower Amu-Darya River, Khorezm, Uzbekistan.

Old riverbed of the Amu Darya, near Nukus.

‘Considering the fact that the desiccation of the Aral Sea is irrigation-driven and the water deficiency has been the direct cause of the economic and ecological disaster in the further downstream areas (e.g., Karakalpakstan), an increase in water-use efficiency in Khorezm is essential for the economic sustainability of the Aral Sea Basin.’

- Ibrakhimov, Mirzakhayot & Park, Soojin & Vlek, Paul. (2004). Development of groundwater salinity in a region of the lower Amu-Darya River, Khorezm, Uzbekistan.

Soviet-style housing in Nukus.

‘Central Asia’s advance into the modern world in the 1920s and 1930s proved considerable … yet Soviet rule also entailed terrible costs and constraints … the volume of publication expanded rapidly in a “linguistic-cultural revolution” that replaced Persian with Tajik and Chaghatay Turkic with Uzbek, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Turkmen and Karakalpak.’

- Carter Vaughn Findley (2005), The Turks in World History, Oxford University Press

Soviet-style housing in Nukus.

‘In the post-Stalin period, even as the Soviet Union postured as defender of the former colonial peoples of the Third World, its colonial-style economic exploitation of Central Asia assumed devastatingly unsustainable forms. In Uzbekistan … monoculture in cotton - “white gold” - was pushed to unsustainable limits, with overuse of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, expansion of irrigation beyond the capacity of the natural water sources, and substitution of cheap local labor, including that of schoolchildren, for mechanization.’

- Carter Vaughn Findley (2005), The Turks in World History, Oxford University Press

Housing blocks in Nukus.

‘As long as the Soviet system lasted, it limited Central Asia’s engagement with modernity in other ways … the long-term goal of this experience, moreover, was supposed to be a reduction of difference into the Russified identity of the idealized “soviet man” … heirs to literary traditions centuries older than the Russians’, the peoples of Central Asia were to accept without criticism the Russian people and culture as models for emulation.’

- Carter Vaughn Findley (2005), The Turks in World History, Oxford University Press

The Amu Darya (in Ancient Greek, the Oxus) in spring, which only flows along this area through an artificial canal. You find the old riverbanks perhaps half a kilometre away in each direction.

‘The Oxus is in spate now since it’s spring

And yet these three with heavy armor ride

Into the waves and reach the other side;

A wise man would have said no man alive

Could brave this mighty current and survive!’

- Abolqasem Ferdowsi, Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, translated by Dick Davis, describing the legendary feat of the warriors Kay Khosrow, Farigis, and Giv, in fording the Oxus. Ferdowsi completed his epic in 1010.

‘“When you see this salt, sad, dark thoughts take you,” he said, explaining that the salt is what is left when water evaporates after intense irrigation. “Nothing grows on salty land. It’s like standing on a graveyard.”’

- Farmer quoted by Sabrina Tavernise, ‘Old Farming Habits Leave Uzbekistan a Legacy of Salt’, New York Times article on 15 June 2008

‘Gurganj stood at the crossroads of four of Central Asia’s main transport routes. The road east passed through the earlier capital, Kath [Khiva], & eventually reached…Otrar & beyond that, Chach [Tashkent], Taraz & Balasagun, before passing into East Turkestan to reach Kashgar & eventually, China itself. The southern road went to Merv, Bukhara, Balkh, Kabul & eventually India, while the caravan route north led up the Volga Valley to the land of the Rus and then to Scandinavia … nowhere on earth were irrigation technologies more highly developed than here.’

- S. Frederick Starr (2013), Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane, Princeton University Press

It’s about a three hour walk from Nukus to the ancient necropolis at Mizdakhan. You can pass through Khujayli, but the salt and mud in the street will cake your boots. It’s Sunday afternoon - all the kids are out in the streets playing soccer, the banks are closed, and the unofficial moneychangers have left the market. I have only US $2 in Uzbek currency and it just covers a ride back to Nukus in the dark. The driver detours to his house to drop off his mother, who gifts me a loaf of very stale Uzbek naan - fluffy (when it’s fresh) circular bread, stamped thin in the middle so the centre becomes crusty, like a cracker. It’s the thought that counts.

Mizdakhan was an urban settlement since the 4th C. BC & a necropolis since the 8th C. AD.

‘A large Mongol trade mission consisting of some 450 Muslim merchants arrived in Otrar. It was stopped by the Khwarizmshah’s governor, who accused the merchants of being Mongol spies, confiscated their property, and executed them…Chinggis sent an embassy to the Khwarizmshah to demand wergild for the murdered men and punishment of the governor responsible…the Khwarizmshah insulted the Mongols and killed the envoys.’

- C.I. Beckwith (2009), Empires of the Silk Road, describing the events that precipitated the Mongol invasion of Khorezm.

Women make their way to a mausoleum, known locally as a fertility shrine, in the old town of Gurganj. Next to the shrine is a small hillock, thought to be the site of an academy founded by Abu Ali Mamun in the 10th Century A.D.

‘The one difference [between Mamun’s academy and the others] is that none of the others could have claimed to include the two greatest minds of the Middle Ages, Biruni and Ibn Sina, not to mention a legion of other major poets, writers and scientists. During its brief existence Mamun’s academy was the intellectual center of the world.’

- S. Frederick Starr (2013), Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane, Princeton University Press

This minaret was likely commissioned by Mahmud of Ghazni in ~1011 AD & restored by the Mongols after razing the city.

‘With virtually unlimited resources in the form of plunder from India, Mahmud could indulge his passion for architecture…No wonder that he boasted (in lines inscribed on his victory tower in Gurganj) that he had created “the glitter of the earthly world”…He typically laid the expense of maintaining his grand edifices on the reluctant local public, so the process of decay began immediately. The cost to the citizens of Balkh for the upkeep of his formal gardens in that city was so burdensome that he first tried to foist it onto local Jews and then lost interest’.

- S. Frederick Starr (2013), Lost Enlightenment

By a canal, looking towards the mosque, in Nukus.

‘Irrigation made arable land a valuable and scarce commodity…[in] centuries of work on the land, surveyor-practitioners in the various oases had worked out methods of measuring regular and irregular fields…it was a natural step for Central Asians to compile the known techniques of geometry, work out the first system of practical algebra, and create the field of trigonometry. The major step in this direction occurred in the ninth century, on the basis of accumulated experience of Khwarazm, the most intensely irrigated region’.

- S. Frederick Starr (2013), Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane, Princeton University Press

Bazaar in Nukus.

‘They reached a fertile and well-watered place,

Possessed of every strength and natural grace:

The setting’s natural limit was the sea,

A highway marked the inland boundary,

To one side mountains reared above the plain,

A place of hunting grounds, and wild terrain;

The streams, the groves of trees, made weary men

Feel that their ancient hearts were young again.’

- Abdolqasem Ferdowsi, Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, translated by Dick Davis. This verse describes the Iranian hero Seyavash founding a city somewhere in Turkestan, at the invitation of Afraysiab the Turk.

Bazaar in Nukus.

‘The tenth-century geographer Mukadasi has left a detailed list of the commodities traded by the merchants of Khorezm…locally produced commodities included: ‘grapes, many raisins, almond pastry, sesame, fabrics of striped cloth, carpets, blanket cloth, satin for royal gifts, coverings of mulham fabric, locks, Aranj fabrics, bows which only the strongest could bend, rakhbin [cheese], yeast, fish, boats' …[also] watermelons so succulent that they were packed into lead containers lined with snow and conveyed to the caliphs of Baghdad…a single melon was worth 700 dirhams - equivalent to more than 2 kg of silver.’

- Jonathan Tucker (2015), The Silk Road: A Travel Companion, I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd

Bazaar in Nukus, fifty kilometres from old Gurganj.

‘Despite its utter destruction, within 100 years Gurganj had risen from the ashes…by the early fourteenth century, Gurganj had been rebuilt to serve the caravans travelling to the Golden Horde territory in the Volga region. Ibn Battuta described newly revived Gurganj as a vigorous commercial centre, ‘the largest, greatest, most beautiful and most important city of the Turks, shaking under the weight of its populations, with bazaars so crowded that it was difficult to pass.’’

- Jonathan Tucker (2015), The Silk Road: A Travel Companion, I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd

Traintracks near the station in Khujayli, with the ever-present salted ground in the foreground.

‘“We are destroying ourselves,” said the 61-year-old farmer in Khujayli. “Why are we planting cotton, and what are we getting from it? We never ask those questions.”’

- Farmer quoted by Sabrina Tavernise, ‘Old Farming Habits Leave Uzbekistan a Legacy of Salt’, New York Times article on 15 June 2008

Petrol station surrounded by salted land in Nukus.

‘Before committing to large and expensive drainage projects, it is essential to remove the distortions in relative prices of crops and water that generate a large part of the problem.’

- Kyle, Steven C. & Chabot, Phillippe (1997), Agriculture in the Republic of Karakalpakstan and Khorezm Oblast of Uzbekistan.

The distortions included unrealistic cotton yield targets set by the state, input (water, fuel, fertiliser, and labour) subsidies, and farmers having to sell their cotton to the state at a discount.

Go-kart track in Nukus.

‘The farmer in Khujayli recalled a car trip with his father in the winter of 1954 near the city of Muynoq that began with a crossing of miles of Aral Sea ice. Now the shore is more than 50 miles away from the city. In the 1970s, his grandfather’s apricot trees died. Salt eats away at shoes here and turns bricks white.’

- Sabrina Tavernise, ‘Old Farming Habits Leave Uzbekistan a Legacy of Salt’, New York Times article on 15 June 2008

The dry riverbed of the Amu Darya near Nukus.

‘Shallow groundwater contributes to salt accumulation through capillary rise, and results in the accumulation of salts at the soil surface ... In agricultural fields, the “critical depth”, which results in the accumulation of salts due to capillary rise, is in the range 1.5-2.0 m below the surface ... the groundwater depth in Khorezm was above the critical level throughout the growing season.’

- Ibrakhimov, Mirzakhayot & Park, Soojin & Vlek, Paul. (2004). Development of groundwater salinity in a region of the lower Amu-Darya River, Khorezm, Uzbekistan.

Old riverbed of the Amu Darya, near Nukus.

‘Considering the fact that the desiccation of the Aral Sea is irrigation-driven and the water deficiency has been the direct cause of the economic and ecological disaster in the further downstream areas (e.g., Karakalpakstan), an increase in water-use efficiency in Khorezm is essential for the economic sustainability of the Aral Sea Basin.’

- Ibrakhimov, Mirzakhayot & Park, Soojin & Vlek, Paul. (2004). Development of groundwater salinity in a region of the lower Amu-Darya River, Khorezm, Uzbekistan.

Soviet-style housing in Nukus.

‘Central Asia’s advance into the modern world in the 1920s and 1930s proved considerable … yet Soviet rule also entailed terrible costs and constraints … the volume of publication expanded rapidly in a “linguistic-cultural revolution” that replaced Persian with Tajik and Chaghatay Turkic with Uzbek, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Turkmen and Karakalpak.’

- Carter Vaughn Findley (2005), The Turks in World History, Oxford University Press

Soviet-style housing in Nukus.

‘In the post-Stalin period, even as the Soviet Union postured as defender of the former colonial peoples of the Third World, its colonial-style economic exploitation of Central Asia assumed devastatingly unsustainable forms. In Uzbekistan … monoculture in cotton - “white gold” - was pushed to unsustainable limits, with overuse of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, expansion of irrigation beyond the capacity of the natural water sources, and substitution of cheap local labor, including that of schoolchildren, for mechanization.’

- Carter Vaughn Findley (2005), The Turks in World History, Oxford University Press

Housing blocks in Nukus.

‘As long as the Soviet system lasted, it limited Central Asia’s engagement with modernity in other ways … the long-term goal of this experience, moreover, was supposed to be a reduction of difference into the Russified identity of the idealized “soviet man” … heirs to literary traditions centuries older than the Russians’, the peoples of Central Asia were to accept without criticism the Russian people and culture as models for emulation.’

- Carter Vaughn Findley (2005), The Turks in World History, Oxford University Press

The Amu Darya (in Ancient Greek, the Oxus) in spring, which only flows along this area through an artificial canal. You find the old riverbanks perhaps half a kilometre away in each direction.

‘The Oxus is in spate now since it’s spring

And yet these three with heavy armor ride

Into the waves and reach the other side;

A wise man would have said no man alive

Could brave this mighty current and survive!’

- Abolqasem Ferdowsi, Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings, translated by Dick Davis, describing the legendary feat of the warriors Kay Khosrow, Farigis, and Giv, in fording the Oxus. Ferdowsi completed his epic in 1010.

‘“When you see this salt, sad, dark thoughts take you,” he said, explaining that the salt is what is left when water evaporates after intense irrigation. “Nothing grows on salty land. It’s like standing on a graveyard.”’

- Farmer quoted by Sabrina Tavernise, ‘Old Farming Habits Leave Uzbekistan a Legacy of Salt’, New York Times article on 15 June 2008

‘Gurganj stood at the crossroads of four of Central Asia’s main transport routes. The road east passed through the earlier capital, Kath [Khiva], & eventually reached…Otrar & beyond that, Chach [Tashkent], Taraz & Balasagun, before passing into East Turkestan to reach Kashgar & eventually, China itself. The southern road went to Merv, Bukhara, Balkh, Kabul & eventually India, while the caravan route north led up the Volga Valley to the land of the Rus and then to Scandinavia … nowhere on earth were irrigation technologies more highly developed than here.’

- S. Frederick Starr (2013), Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane, Princeton University Press

It’s about a three hour walk from Nukus to the ancient necropolis at Mizdakhan. You can pass through Khujayli, but the salt and mud in the street will cake your boots. It’s Sunday afternoon - all the kids are out in the streets playing soccer, the banks are closed, and the unofficial moneychangers have left the market. I have only US $2 in Uzbek currency and it just covers a ride back to Nukus in the dark. The driver detours to his house to drop off his mother, who gifts me a loaf of very stale Uzbek naan - fluffy (when it’s fresh) circular bread, stamped thin in the middle so the centre becomes crusty, like a cracker. It’s the thought that counts.

Mizdakhan was an urban settlement since the 4th C. BC & a necropolis since the 8th C. AD.

‘A large Mongol trade mission consisting of some 450 Muslim merchants arrived in Otrar. It was stopped by the Khwarizmshah’s governor, who accused the merchants of being Mongol spies, confiscated their property, and executed them…Chinggis sent an embassy to the Khwarizmshah to demand wergild for the murdered men and punishment of the governor responsible…the Khwarizmshah insulted the Mongols and killed the envoys.’

- C.I. Beckwith (2009), Empires of the Silk Road, describing the events that precipitated the Mongol invasion of Khorezm.

Women make their way to a mausoleum, known locally as a fertility shrine, in the old town of Gurganj. Next to the shrine is a small hillock, thought to be the site of an academy founded by Abu Ali Mamun in the 10th Century A.D.

‘The one difference [between Mamun’s academy and the others] is that none of the others could have claimed to include the two greatest minds of the Middle Ages, Biruni and Ibn Sina, not to mention a legion of other major poets, writers and scientists. During its brief existence Mamun’s academy was the intellectual center of the world.’

- S. Frederick Starr (2013), Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane, Princeton University Press

This minaret was likely commissioned by Mahmud of Ghazni in ~1011 AD & restored by the Mongols after razing the city.

‘With virtually unlimited resources in the form of plunder from India, Mahmud could indulge his passion for architecture…No wonder that he boasted (in lines inscribed on his victory tower in Gurganj) that he had created “the glitter of the earthly world”…He typically laid the expense of maintaining his grand edifices on the reluctant local public, so the process of decay began immediately. The cost to the citizens of Balkh for the upkeep of his formal gardens in that city was so burdensome that he first tried to foist it onto local Jews and then lost interest’.

- S. Frederick Starr (2013), Lost Enlightenment